Throughout the history of financial markets, various colourful and interesting personalities are known to dominate various cycles, appearing as 'wizards' or narrative icons of various powerful market trends.

Think about the 1980s for a moment. Both Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were sworn into office in the United States and in Great Britain and both advocated deregulation and free trade policies, enabling a boom in financial assets in the Western developed markets. The late John Gutfreund and Lewis Ranieri were running Salomon Brothers, and it was the "Greed is Good" era, where the narrative was fed by Michael Milken, Ivan Boesky, Martin Zweig, and the image of the flamboyant and outspoken investment banker in Winchesters and suspenders became synonymous with Wall Street culture - the archetype being Gordon Gekko.

During the days of the late 1990s and the Tech Bubble, the zeigeist and animal spirits of that time were lifted by characters like Henry Blodget, Jack Grumman, Frank Quattrone and Mary Meeker. Back then, the techno-preneurs like Paul Graham, Elon Musk, Peter Thiel and Larry Page were working hard on their projects and startups, and are now successful Venture Capitalists or business owners in their own right.

Then there were the days of the 2000s. The decade between 2000 to 2010 saw 2 huge booms (or bubbles depending on how one views them), one in the US housing market, which led to the collapse in subprime mortgages, and the other, the famous commodity boom. The housing bubble era was fostered by the likes of Louis Cavalier and Abby Joseph Cohen. The emerging markets/commodity boom narrative were led by Jim O'Neil (who coined the term BRICs), Jim Rogers, Marc Faber, T.Boone Pickens, Peter Schiff and Eric Sprott.

Fast forward to the present day, and we get a whole new host of icons in the present cycle. Only this time, they are leading academics and economists, and are running (or advising) various central banks around the world. This new narrative of omnipotence are led by the likes of Paul Krugman, Ben Bernanke, Mark Carney, Haruhiko Kuroda, Janet Yellen and Mario Draghi. These powerful figures have an almost all-encompassing presence and influence in the global financial markets as we speak.

We initially started this decade with the belief that central banks could solve the issue of a lethargic and slow economy since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. And everyone relied on these leading policy-makers.

Perhaps, the current narrative could be the real truth, and these characters could continue to be the trend guardians. However, the frightening truth is what if the narrative does not play out in the way they expect it to be?

Already, we are seeing some signs of central bankers losing their grips over the markets. In Europe and Japan, the imposition of a negative interest rate policy on deposits park at their respective central banks' facilities have not had the desired effect that policy-makers desire for (perhaps we need more time, but how long more?).

Consider that in both the European continent as well as Japan, both the Euro and the Japanese Yen currencies have been strengthening relative to their trade partners. Additionally, European banks are parking more money at the European Central Bank (ECB) despite them having to pay more on those deposits. In Japan, consumers and households are hoarding cash instead of investing or spending, which is entirely against what the Abe-regime hopes for.

At the same time, the US Federal Reserve seems to be backtracking on its expected path of tightening via hikes in the benchmark Fed Funds rates - perhaps to soften the US dollar and to alleviate concerns of the international community. And the Fed seems to have internal dissent as well, with several more 'hawkish' members of the committee expressing their concerns on a deviation from the central bank's targets.

What and how do we make of this?

It is entirely possible that we are at an inflection point in this decade - that central banks may be facing a 'crisis' and that more people increasingly do not buy the fact that central bankers are really in control.

Some time in the future, we may look back in history and characterize this decade as the "Central Bank Decade"...

Wednesday 30 March 2016

Saturday 26 March 2016

The Saudi Riyal Peg - Sustainable For Now?

The hefty plunge in crude oil prices since the second half of 2014 have wrecked countries heavily reliant on energy-related exports, leading to GDP downgrades by economists and contraction of growth since then. Emerging markets like Russia, Nigeria and Venezuela are probably some of the most-affected, and the impact is clearly evident from the sharp depreciation of their respective currencies vis-à-vis hard currencies like the US Dollar.

This development has raised concerns over the economic health of Saudi Arabia - clearly (and still) the world's most important crude oil exporter and the somewhat-defacto leader of the OPEC cartel. With lower oil revenues, the kingdom has cut expenditures and raise funds (via tapping the bond market or digging into its sovereign wealth entities) in order to maintain the current status quo. News that Saudi Aramco, the state-owned oil giant, is going public has also gotten market participants curious and looking beyond the veil in their attempt to ascertain the state of finances and affairs of the Middle Eastern kingdom.

One key issue that came up was whether the kingdom could maintain its currency peg against the US Dollar. Where it once was an unquestionable fact the past 3 decades, the markets are now speculating on the sustainability of the current level of the Riyal's peg against the US Dollar - which currently stands at 3.75 (USD/SAR).

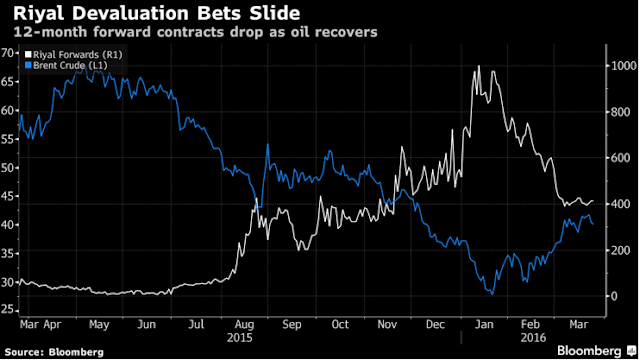

Policy-observers, market cynics and analysts have cited that both trade and budget deficits are increasing pressures on the kingdom, after being used to years of running surpluses. Forward contracts in December 2015 and early 2016 show that the market expects a downward adjustment of the SAR against the USD (although the recent rebound in crude oil prices have tapered expectations), and betting against the SAR is cheap and contains an asymmetric risk/reward profile (expected upside more than downside), making the trade attractive.

To understand the probability of this event, it is imperative to analyse the possible outcomes, and to examine its possible effects to the Saudis. Should a devaluation occur (whether it's through a gradual downward adjustment of the currency peg or a total abandonment):

(i) short-term relief on the state's finances and improve the balance of payments, since most of the government's expenses are denominated in SAR while their revenues are USD-denominated (like oil receipts). It could also increase export-competitiveness. However, this is not a long term strategy as import costs will surge, and this could lead to high imported inflationary pressures reducing purchasing power as the kingdom relies heavily on imports!

(ii) capital outflows could accelerate as markets question once again if a lower rate is sustainable. A drastic change to the USD peg would require deliberate planning and communication and a reliable monetary policy framework to gain confidence and credibility.

With the above understanding, the probability of maintaining the peg is still high (at least > 80%) until end-2017 given that a devaluation may not be in their best interests. The Saudis are also taking measures to revamp and modernize their economy (which is way less diversified than Canada and even Russia). The kingdom is also in the midst of planning and implementing structural changes to their budget and fiscal plans.

Moreover, they still have the resources and leeway to adjust themselves to the new reality and the current environment. Saudi Arabia is not in a similar state like the United Kingdom was in 1992 during the Sterling Crisis when the country was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). Foreign exchange reserves are still relatively large, and they have time to adapt - consider:

(i) as of end-2015, M2 supply was USD 421 billion (SAR 1.58 trillion), against reserves of USD 604 billion - making the coverage ratio 1.41 - sufficient to maintain the peg.

(ii) the government is expected to shift towards higher debt financing, exploring the options of raising external debt in both international loan and capital markets. Domestic commercial banks will probably be incentivised to hold a larger share of sovereign bonds.

Additionally, there is the troubling geopolitical state of affairs to consider at this current juncture. With Iran now being reintegrated into the global economy, the country is ramping up its crude oil exports, and their main rival in the region is Saudi Arabia. This makes the Saudis reluctant to give up defending their market share in crude oil exports, keeping in mind the surprising resiliency of the US shale energy industry at the moment.

Tensions remain elevated in the Middle East, with traditionally peaceful countries like Jordan and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) actually deploying armed forces to troubled areas like Syria and eastern Libya, and the United States of America (USA) desperate to retain its declining influence over the region while erstwhile supporting Israel. There is a possibility that US policy-makers could arrange a swap agreement with the Saudis (their ally) to allow them to maintain the currency peg should they find themselves unable to do so, as social or civil unrest in the kingdom following high inflation from a Riyal devaluation could lead to chaos in Saudi Arabia, which could possibly lead to a decrease of America's influence in the region.

Unlike the British in 1992, the Saudis could actually choose when to adjust the Riyal's peg should they wish to. If any, an abandonment of the current level remains a grey swan event.

At least for now ...

This development has raised concerns over the economic health of Saudi Arabia - clearly (and still) the world's most important crude oil exporter and the somewhat-defacto leader of the OPEC cartel. With lower oil revenues, the kingdom has cut expenditures and raise funds (via tapping the bond market or digging into its sovereign wealth entities) in order to maintain the current status quo. News that Saudi Aramco, the state-owned oil giant, is going public has also gotten market participants curious and looking beyond the veil in their attempt to ascertain the state of finances and affairs of the Middle Eastern kingdom.

One key issue that came up was whether the kingdom could maintain its currency peg against the US Dollar. Where it once was an unquestionable fact the past 3 decades, the markets are now speculating on the sustainability of the current level of the Riyal's peg against the US Dollar - which currently stands at 3.75 (USD/SAR).

Policy-observers, market cynics and analysts have cited that both trade and budget deficits are increasing pressures on the kingdom, after being used to years of running surpluses. Forward contracts in December 2015 and early 2016 show that the market expects a downward adjustment of the SAR against the USD (although the recent rebound in crude oil prices have tapered expectations), and betting against the SAR is cheap and contains an asymmetric risk/reward profile (expected upside more than downside), making the trade attractive.

To understand the probability of this event, it is imperative to analyse the possible outcomes, and to examine its possible effects to the Saudis. Should a devaluation occur (whether it's through a gradual downward adjustment of the currency peg or a total abandonment):

(i) short-term relief on the state's finances and improve the balance of payments, since most of the government's expenses are denominated in SAR while their revenues are USD-denominated (like oil receipts). It could also increase export-competitiveness. However, this is not a long term strategy as import costs will surge, and this could lead to high imported inflationary pressures reducing purchasing power as the kingdom relies heavily on imports!

(ii) capital outflows could accelerate as markets question once again if a lower rate is sustainable. A drastic change to the USD peg would require deliberate planning and communication and a reliable monetary policy framework to gain confidence and credibility.

With the above understanding, the probability of maintaining the peg is still high (at least > 80%) until end-2017 given that a devaluation may not be in their best interests. The Saudis are also taking measures to revamp and modernize their economy (which is way less diversified than Canada and even Russia). The kingdom is also in the midst of planning and implementing structural changes to their budget and fiscal plans.

Moreover, they still have the resources and leeway to adjust themselves to the new reality and the current environment. Saudi Arabia is not in a similar state like the United Kingdom was in 1992 during the Sterling Crisis when the country was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). Foreign exchange reserves are still relatively large, and they have time to adapt - consider:

(i) as of end-2015, M2 supply was USD 421 billion (SAR 1.58 trillion), against reserves of USD 604 billion - making the coverage ratio 1.41 - sufficient to maintain the peg.

(ii) the government is expected to shift towards higher debt financing, exploring the options of raising external debt in both international loan and capital markets. Domestic commercial banks will probably be incentivised to hold a larger share of sovereign bonds.

Additionally, there is the troubling geopolitical state of affairs to consider at this current juncture. With Iran now being reintegrated into the global economy, the country is ramping up its crude oil exports, and their main rival in the region is Saudi Arabia. This makes the Saudis reluctant to give up defending their market share in crude oil exports, keeping in mind the surprising resiliency of the US shale energy industry at the moment.

Tensions remain elevated in the Middle East, with traditionally peaceful countries like Jordan and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) actually deploying armed forces to troubled areas like Syria and eastern Libya, and the United States of America (USA) desperate to retain its declining influence over the region while erstwhile supporting Israel. There is a possibility that US policy-makers could arrange a swap agreement with the Saudis (their ally) to allow them to maintain the currency peg should they find themselves unable to do so, as social or civil unrest in the kingdom following high inflation from a Riyal devaluation could lead to chaos in Saudi Arabia, which could possibly lead to a decrease of America's influence in the region.

Unlike the British in 1992, the Saudis could actually choose when to adjust the Riyal's peg should they wish to. If any, an abandonment of the current level remains a grey swan event.

At least for now ...

Labels:

Crude,

Currency,

Middle East,

Oil,

Riyal peg,

Saudi Arabia,

US,

USDSAR

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)