It chronicles the history of the tallest skyscrapers ever built on earth. Now, look at the years they were completed. Notice anything interesting? Here's a hint: historically, each new skyscraper coincided with the end of an economic boom associated with it... a hallmark that signifies the end of an era. The completion of the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building both coincided with the end of the 1920s boom in the US, signifying the start of the infamous Great Depression of the 1930s. The Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur was completed after the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 broke out, after many Asian economies experienced a period of strong GDP growth rates and a financial boom...

This is what The Economist calls the "Skyscraper Effect" (for more information about it, the Mises Institute has some interesting thoughts).

Now, Saudi Arabia is building the world's tallest skyscraper. Known as the Jeddah Tower, it would be at least 170m higher than the Burj Khalifa in next door Dubai and at least 3 times higher than the Chrysler Building in New York. Costing about US$ 1.5 billion, it is estimated to be completed in 2018/2019, and will be surrounded by a supersized mall and an artificial lake (which brings adds another US$ 20 billion to the development tab). The CEO of the project, Mounib Hammoud, says that "it's a statement of power, of economic growth, of success."

Courtesy of the Wall Street Journal:

Would the Jeddah Tower once again mark the end of a cycle? Or is the skyscraper effect just plainly a mere coincidence? Too some however, the skyscraper effect makes economic sense. Historically, the development projects were drawn up during a period of prosperity, in times of great optimism. The actual construction takes a long period of time to play out before its final completion. By the time the new development is completed, the "boom" and all the accompanying euphoria has evaporated.

Now with the above being mentioned, let's turn our attention back to the current state of affairs.

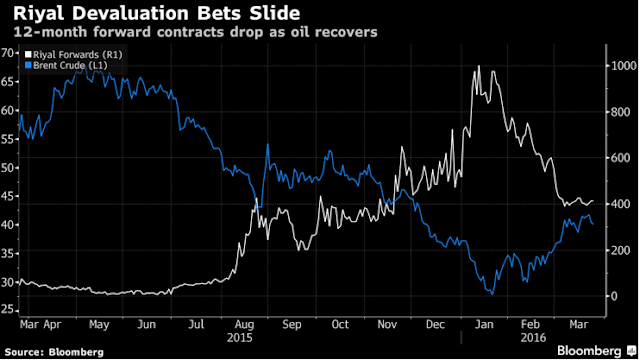

Since the start of the fall of 2014 when crude oil prices have plunged from above US$100/barrel to below US$30/barrel in early 2016 (they are currently hovering above US$40/barrel), OPEC nations have maintained and even increased their production amount, with the Saudis leading the pack in an attempt to drive higher-cost producers out of business (such as those cowboys in North America).

However, their attempts to crush the North American marginal producers may have backfired. In the mid-1980s, the Saudis expanded production to drown out their US competitors (which worked beautifully back then). When the damage has been done, the Saudis cutback output to tighten supplies, sending crude oil prices soaring back up.

However, this time round, US crude oil production remain surprisingly resilient. Despite a slight slowdown in output, many producers in the US have opted to maintain and even increase their production. The US Department of Energy's data still indicates that production remains close to 9 million barrels daily.

And this is despite the following developments (to the dismay of oil bulls):

The amount of petroleum freight carloads according to the Association of American Railroads has declined -36.3% from its 2014-highs, indicating that energy production from shale rock formations did slow down (rail freight is one better way to track production activity among shale energy producers as railroads had to step up to fill the gap created as domestic production outpaced existing pipeline capacity during the shale energy boom).

Rig count data tracked and compiled by Baker Hughes has fallen substantially in North America, but that has not led to a further cut in output - the white line being the rig count, which currently stands around 340, at multi-year lows and at a quarter of its 2014 peak.

There are several possible reasons for the continued expansion of oil production in the US:

- the energy sector is heavily reliant on credit. When times were good, credit flooded the sector, allowing many producers, including the non-conventional shale companies to ramp up output. In fact, Canada's oil sands' boom was largely built on credit. An entire industry fueled by cheap credit is difficult to end, as producers have to continue producing to service their debt obligations in order to keep the credit taps flowing and to stay in business. The Saudis may have miscalculated, and did not anticipate the effect of the cheap credit cycle on the North American energy industry. The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) have actually reported on this, commenting that the crude oil market is so broken that low prices may actually make the supply glut worse.

- the costs of producing a barrel of crude oil varies widely in various areas of the the US (based on initial costs of exploration and production, as well as financing and maintenance costs). Some of the recent output has actually been generated from "stripper" wells, which were once abandoned sites that are seeing new life thanks to advanced production techniques, and these wells are profitable at current prices. Additionally, some of the rigs that have been sidelined, thereby contributing to the fall in aggregate rig counts, were either "newer" sites or less efficient operations

- Some producers may be better off maintaining output as they may incur more losses if they shut operations down. The high cost of terminating and restarting may even spur them to produce more now and store the surplus, ready to deploy their reserves the minute crude oil prices rebound sufficiently higher. Inventories at Cushing, Oklahoma are at decade highs!

Meanwhile, data from the International Energy Agency indicated that total stockpiles among OECD countries are also at multi-year highs, presenting a huge headache for anyone hoping for a strong lasting rebound in crude oil prices (unless stockpiles dwindle, high crude oil prices may be unsustainable as supplies are dumped to capture price increases):

While Wood Mackenzie reported that indeed some cutbacks have been made in onshore fields in Canada, as well as aging North Sea fields, OPEC producers in the Middle East have kept the taps on and contributed to the current global glut... So this essentially is terrible news to the Saudis in their attempt to regain market share since they started this painful campaign of attrition.

Let's digress once more, and think from a game-theory perspective.

Many of us have played poker before. Professional poker players and experts will tell you that it's all a game of probability and odds. Winning at poker essentially requires a superior understanding of the odds and playing your hand well, and also being proficient at reading or anticipating the motives of the players you're up against.

To better understand the current dynamic of the crude oil market, it would thus be wise and even imperative to consider what the Saudis are doing at this moment:

Let's digress once more, and think from a game-theory perspective.

Many of us have played poker before. Professional poker players and experts will tell you that it's all a game of probability and odds. Winning at poker essentially requires a superior understanding of the odds and playing your hand well, and also being proficient at reading or anticipating the motives of the players you're up against.

To better understand the current dynamic of the crude oil market, it would thus be wise and even imperative to consider what the Saudis are doing at this moment:

- they have set up a whopping US$ 2 trillion investment fund in an attempt to diversify their economy away from hydrocarbons and to generate alternative revenue streams over the next 5 - 10 years

- they have cut expenditures in latest budget adjustments, and tapped the debt markets for a portion of their financing requirements. Via Bloomberg: "the country's ratio of debt to economic output, the world's lowest in 2014, is expected to increase to over 25% by 2017, according to the International Monetary Fund, which said in October that the kingdom risked wiping out its financial reserves in 5 years"

- they have even decided to overhaul their military in the process! (this is despite their ongoing military operation in Yemen)

And these developments above are done by the "smartest of the smart money" of the global crude oil industry. If there exists any form of "insider-info" in the industry, then the Saudis are probably the guys who know them best - and this smart money is boldly preparing to hunker down for a prolonged period of low oil prices. Doesn't this send a troubling signal to anyone who is optimistic that crude oil prices could recover higher and also stay higher?

The investment community seems not to agree. Even after the failure of the recent Doha talks, crude oil prices have risen, with both WTI and Brent crude prices above US$40 per barrel. Open interest futures positioning by speculators (black line) and the hedgers (yellow line) seems to suggest that the speculative community is betting on a rebound in crude oil prices:

Additionally, there is the sticky problem of Iran's reintegration into the global economy. The Iranians have vowed to only enter high-level negotiations and summits only after they have regained their former market share of the crude oil export market. And look at how the Saudis reacted to them at the recent Doha talks? To the geopolitical observer, the animosity between these 2 rivals in the Gulf is no surprise.

All of the above leads us to this chain of logic:

-> "Strategy of drowning out the competition is taking longer-than-expected, but it would be worse to give up now, let's continue to produce and finish the job!

-> If the strategy will take longer than expected to work out, we have to prepare and hunker down for as long as it takes!

-> No negotiations or concessions for any of my rivals until the strategy works out! Antagonise and block any bids for new market share! (the Saudis have openly talked about their extra 1 million barrels/day output potential openly and have promised to use it)"

Considering this chain of logic with the understanding that the crude oil industry is Saudi Arabia's lifeblood makes it all the more frightening - they have every reason to execute their current game plan to the end as the whole game involves their existence on this planet.

Now that the facts have been laid above, the fundamentals clearly show that the odds to the fate of crude oil prices remain to the downside, and any upward spike or rebound may not be sustainable at all.

Stay tuned for Part II!

P.S.: Remember our new Jeddah Tower mentioned earlier? Would it perhaps mark the end of Black Gold.. perhaps, as Mercenary Trader puts it: an R.I.P. marker/tombstone for the hydrocarbon age?